- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Europe

What Really Caused the Eurozone Crisis?

By Daniel Gross and Richard Baldwin

Like other observers, Richard Baldwin and Daniel Gros believe the most recent Eurozone crisis shouldn't be classified as a government debt crisis, even though it evolved into one. Instead, they think EU experienced a 'sudden-stop crisis with monetary union characteristics.'

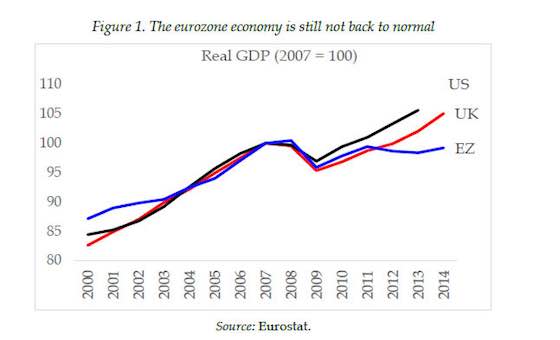

Europe has been in crisis mode for more than five years now. There are signs that the eurozone (EZ) economy is recovering, but it is far from being back to normal (see Figure 1, below).

Eurozone Economy Graph 1

When we published an eBook on vox.eu in June 2010, just at the beginning of the EZ crisis, one of the authors, Charles Wyplosz, wrote:

the Eurozone is levitating on the hope that European leaders will find a way to end the crisis and take steps to avoid future ones. Unless more is done, however, this levitation magic will wear off and the Eurozone crisis will resume its destructive, unpredictable path.

Now, more than five years later, this prediction has turned out to be accurate. The situation was deteriorating until decisive steps were taken to stabilise financial markets. But many of the weaknesses and imbalances that caused the EZ crisis are still in evidence:

- Many of Europe’s banks face problems of non-performing loans;

- Many are still heavily invested in their own nation’s public debt – a bind that means problems with banks threaten the solvency of the government and vice versa;

- borrowers across the continent are vulnerable to the inevitable normalisation of interest rates that have been close to zero for years

If we want to understand the persistent under-performance of the EZ economy we need to look at what caused the EZ crisis in the first place.

In a consensus narrative of the causes, we, along with 14 others, assert that in its origin, the EZ crisis should not be thought of as a government debt crisis – even though it evolved into one. It was a sudden-stop crisis with “monetary union characteristics” (See “Rebooting the Eurozone: Step 1 – Agreeing a Crisis Narrative”). Most of our 14 co-authors also penned their individual views in the eBook.

Causes of the EZ crisis

In 2007, the eurozone was a crisis waiting to happen. During the early ‘good years’ of the euro – when most considered it as a good if not a great thing – massive imbalances built up, largely unnoticed. Indeed, at the time this was viewed as a positive feature, not as a flaw. Big capital flows from EZ core nations like Germany, France and the Netherlands to EZ periphery nations like Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Greece were taken as evidence that the euro was fostering real convergence between a slow-growing core and more dynamic periphery economies.

The problem was that this meant that the periphery was relying on foreign lenders to cover the savings-investment gap. When the Global Crisis broke out in 2008, those foreign investors got cold feet. They stopped lending across borders.

This triggered a “sudden stop with monetary-union characteristics”. That is, it did not – as in the case of Iceland – manifest itself as an abrupt implosion (see Danielsson, 2008). The EZ’s target system automatically prevented this. Rather, it showed up in rising risk premiums.

- The abrupt end of capital flows raised concerns about the viability of banks and governments in nations dependent on foreign lending, i.e. those running current account deficits.

- Slowing growth produced big deficits and rapidly increasing public debt ratios.

- When things got bad enough, several governments had to take on some of their banks’ debt, thereby increasing national debt ratios even further.

This is how a balance of payments crisis turned into a public debt crisis.

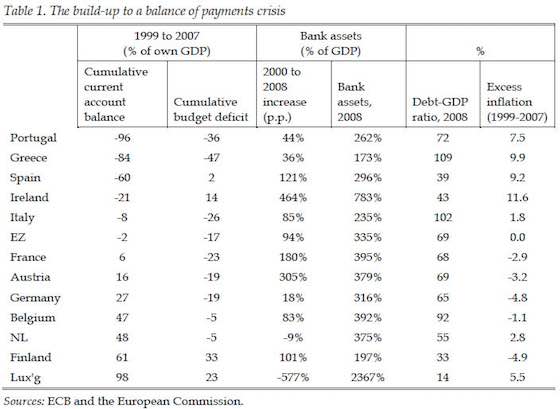

Importantly, there is no good reason to view this as a classic case of profligate spending by governments (apart from in Greece).

- With the exception of Greece, the nations that ended up with bailouts were not those with the highest debt-to-GDP ratios.

- Belgium and Italy sailed into the crisis with public debts of about 100% of GDP and yet did not end up with Troika programmes.

- Ireland and Spain, with ratios under 40%, needed bailouts.

Balance of Payments Graph 2

The real culprits were the large intra-EZ capital flows that occurred in the decade before the crisis. These imbalances baked problems into the EZ ‘cake’ that would spill over in the 2010s. All the nations stricken by the crisis were running current account deficits. None of those running current account surpluses were hit.

Why EZ membership mattered: Crisis amplifiers

Monetary union mattered since it allowed cross-border imbalances to get so big during the boom (‘within a monetary union current accounts do not matter’). But it also mattered when the cross-border flows suddenly stopped. The common payments system provided some automatic liquidity cushion (the famous TARGET imbalances), but incomplete institutional infrastructure amplified the initial loss of trust in the deficit nations in various ways.

- EZ governments that ran into trouble had no lender of last resort.

Without a lender of last resort, a small sustainability shock could be endlessly amplified due to the deadly helix of rising risk premiums and deteriorating budget deficits stemming from higher debt servicing costs. This debt-default-risk vortex pulled in Portugal and came close to pulling in Italy, Spain and Belgium. Even France and Austria drifted into debt vortexes at the height of the crisis.

- The close links between EZ banks and national governments greatly amplified and spread the crisis.

This is the so-called ‘doom loop’ – the potential for a vicious feedback cycle between banks and their governments. It was one of the key reasons that a single surprise in Greece could escalate into a systemic crisis of historic proportions.

- The predominance of bank financing transmitted bank problems to the wider economy.

As the doom loop and slowing economy heightened uncertainty, investment suffered much more than in countries where bank financing is less central, such as in the US. This weakened economies, thus worsening the outlook for banks as well.

Taken together, these features meant that their euro-denominated borrowing was akin to foreign currency debt in a traditional, developing nation ‘sudden stop’ crisis.

- The other classic crisis response: devaluation, was impossible for euro-using nations.

Moreover, the rigidity of factor and product markets made the process of restoring competitiveness slow and painful in terms of lost output.

The whole situation was made much worse by poor crisis management. Mistakes were made, but above all there was nothing in the EZ institutional architecture to deal with a crisis on this scale. EZ leaders faced the dual challenge of fire-fighting and institution-building – all at a time when the interests of debtors and creditors diverged sharply and European electorates were following developments closely.

Judging from market reactions, each policy intervention ‘saved the day’ but made things worse from the next day on. Only in the summer of 2012 was the corner turned with the decision to set up a banking union and the “whatever it takes” assertion by ECB President Mario Draghi. From then on the doom loop began to work in a positive sense: each reduction in risk spreads made banks and the economy stronger, thereby strengthening the fiscal position of the peripheral countries and justifying further reductions in risk premia. The large bond-buying programme of the ECB is another reason that financial market tensions have largely disappeared.

Conclusion

The fact that the doom loop has turned around for a while should not lead to complacency. The feedback mechanisms between weak sovereigns, banks and the economy still exist. This is what we wrote in June 2010:

The Eurozone ‘ship’ is holed below the waterline. The ECB actions are keeping it afloat for now, but this is accomplished by something akin to bailing the water as fast as it leaks in. European leaders must very soon find a way to fix the hole.

It is time to put national differences aside and finish the job of restoring stability and prosperity in Europe. While the European flotilla may have run aground, it need not sink. But rescuing the Eurozone will require coordination, teamwork, and discipline.

While important progress has been made with the banking union and new institutions like the ESM, it is still true that more needs to be done. We find ourselves at a quiet time; the EZ crisis is in remission. But when interest rates start to rise, or if confidence evaporates again due to global shock, the systemic cracks could reappear at an alarming rate.

References

Baldwin, Richard, Thorsten Beck, Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Olivier Blanchard, Giancarlo Corsetti, Paul de Grauwe, Wouter den Haan, Francesco Giavazzi, Daniel Gros, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, Stefano Micossi, Elias Papaioannou, Paolo Pesenti, Christopher Pissarides, Guido Tabellini and Beatrice Weder di Mauro (2015), “Rebooting the Eurozone: Step 1 – Agreeing a Crisis narrative”, CEPR Policy Insight, No.85 ( http://www.voxeu.org/sites/default/files/file/Policy%20Insight%2085.pdf )

Baldwin, Richard and Daniel Gros (2010), “New eBook: Completing the Eurozone rescue: What more needs to be done?”, VoxEU.org

( http://www.voxeu.org/ content/completing-eurozone-rescue-what-more-needs-be-done )Danielsson, Jon (2008), “How bad could the crisis get? Lessons from Iceland”, VoxEU.org, November 12th ( http://www.voxeu.org/article/how-bad-could-crisis-get-lessons-iceland) .

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Article: Courtesy The International Relations & Security Network.

"What Really Caused the Eurozone Crisis?"