- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Politics

by Kenneth T. Walsh

Leaders from the Start

The 100-day standard for gauging presidential effectiveness is not a perfect measure, but it's a useful one.

The underlying truth is that presidents tend to be most effective when they first take office, when their leadership style seems fresh and new, when the aura of victory is still powerful, and when their influence on Congress is usually at its height.

There is nothing magic about the number, and many presidential aides over the years have complained that it is an artificial yardstick. But it has been used by the public, the media, and scholars as a way to assess presidential success and activism since Franklin Roosevelt pioneered the 100-day concept when he took office in 1933.

Here is a look at the most far-reaching 100-day periods in presidential history.

George Washington

Before the concept of a "first 100 days" entered the popular imagination, there was George Washington, the original precedent setter for the American presidency. He took over the reins of government as the nation's first chief executive in an atmosphere of enormous uncertainty, because many Americans wondered if the new nation could survive. And while Washington's agenda wasn't nearly as extensive as modern presidents', his first 100 days were important because everything he did set a standard for his successors and for the country at large.

Among the problems he faced were the different economies and agendas of the individual states, how to pay down the debt from the Revolution, and the military threats from Britain and other foreign powers. In his inaugural speech on April 30, 1789, Washington acknowledged the challenges ahead as he made "a fervent supplication to the Almighty Being"--a prayer that he and his 4 million fellow citizens would somehow find their way.

"Revered for his honor, a virtue seldom invoked today outside military circles, his peerless standing was based less on his words--he was challenged as a writer and public speaker--than his deeds," writes author Mark Updegrove in Baptism by Fire. "As president, he remained above partisan fray and popular opinion, always acting in what he saw as the best interest of the country. His cabinet contained a mix of Federalists and Anti-Federalists (or Republicans), whose major disagreement was how much power should be given to the national government and how much reserved for the states." America's leaders have been debating the same issues ever since.

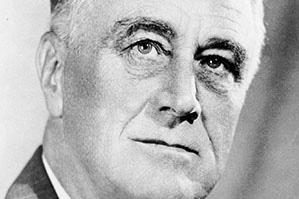

Franklin Roosevelt

Faced with the spreading catastrophe of the Depression in 1933, Franklin Roosevelt knew from the start that what Americans wanted most of all was reassurance that, under his leadership, they could weather the storm. Amid shattering rates of unemployment, bank failures, and a widespread loss of confidence, FDR said in his inaugural speech March 4: "This nation asks for action, and action now. Our greatest primary task is to put people to work. I am prepared under my constitutional duty to recommend the measures that a stricken nation in the midst of a stricken world may require."

Thus began an unprecedented period of experimentation during which Roosevelt tried different methods to ease the Depression; if they failed, he tried something else. His success in winning congressional approval became the stuff of legend and established FDR as the most effective president in dealing with Congress during the first 100 days.

The circumstances that Roosevelt faced were unique.

Banks were shutting down. Depositors were losing their life savings. Businesses were running out of cash to keep going. At least 25 percent of U.S. workers were unemployed. Many Americans felt it was a national emergency.

Roosevelt immediately called Congress into special session and kept it there for three months. He found that the Democrats who were in control were eager to do his bidding, and even some Republicans were cooperative. Raymond Moley, a member of FDR's inner circle, said many legislators "had forgotten to be Republicans or Democrats" as they worked together to relieve the crisis.

FDR quickly won congressional passage for a series of social, economic, and job-creating bills that greatly increased the authority of the federal government. In all, he got 15 major bills through Congress in his first 100 days. "Congress doesn't pass legislation anymore--they just wave at the bills as they go by," said humorist Will Rogers. This was only part of a vast array of government programs that Roosevelt called the New Deal, and collectively they represented a revolution as the nation shifted from a limited central government to an extremely powerful one. Through it all, FDR bonded with everyday Americans with his speeches and "fireside chats," homespun radio talks that reached millions of listeners.

Historians still debate whether FDR's programs actually helped to end the Depression or whether it was World War II that did the trick.

He created a government safety net for people who were down on their luck, and it's clear in retrospect that some of his ideas worked better than others.

But it's also clear that FDR fundamentally expanded the reach and power of the federal government, which most Americans now accept, especially in times of crisis.

And that marked a monumental change in American life.

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman never had a burning desire to be president.

Even when he suddenly took office upon the death of Franklin Roosevelt, he did it not to fuel his ego but out of a sense of duty because as vice president, he was first in the line of succession.

While FDR had pushed through record amounts of legislation during his first 100 days, Truman knew he could not match that total. But he realized his initial months in office would be just as crucial to getting his administration off to a good start.

He started with a burst of decisions.

After being sworn in on April 12, he decided to proceed with the United Nations organizing conference April 25 in San Francisco.

In a radio speech to the nation, given before a joint session of Congress on April 16, Truman promised to pursue FDR's objective of unconditional surrender by Germany and Japan. He retained Roosevelt's cabinet. Every night in the White House, Truman read endless memos and files to ready himself for the choices he was facing.

He gave particular emphasis to foreign affairs in preparation for his upcoming conference in Potsdam, Germany, with Winston Churchill of Britain and Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union.

Shortly after Truman took office, Germany did surrender unconditionally, but Japan fought on.

Thirteen days after he became president, Truman received a detailed briefing from Secretary of War Henry Stimson on the development of the atomic bomb.

On July 25, after he was informed that the first test of the weapon had shown its enormous destructive force, he confirmed an order to use the bomb against Japan. He wanted to force Tokyo to surrender unconditionally and to spare the United States from making what his military planners said would be a horrendously costly invasion of the Japanese homeland.

"I could not bear this thought," Truman said, "and it led to the decision to use the atomic bomb."

Bombs were dropped on Hiroshima August 6 and Nagasaki August 9. An estimated 150,000 civilians died. The Japanese surrendered August 14.

There were many other problems, including how to contain the Soviet Union and how to rebuild the economy in peacetime. So it wasn't long before Truman fully realized the burdens he carried, and he started referring to the White House as the "big white jail." On one occasion, he said, "Being a president is like riding a tiger. You have to keep on riding or be swallowed."

But in his first 100 days, he showed his decisiveness, his intelligence, and his personal sense of duty. And those became the hallmarks of the Truman era.

Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Johnson had a specific objective in mind that guided his presidency from the start -- to outdo Franklin Roosevelt as the champion of everyday Americans.

Johnson had come into office by succession after John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963. He sought to capitalize on the murder by moving swiftly to continue JFK's legacy.

In his first speech to a joint session of Congress on Nov. 27, 1963, five days after the assassination, Johnson asked for support in completing Kennedy's stalled agenda.

He hailed his martyred predecessor as "the greatest leader of our time" and said, "Let us begin. Let us continue."

Johnson had been a consummate legislative deal maker before Kennedy chose him to balance the ticket as his vice presidential running mate in 1960. But Johnson, a longtime senator from Texas, was never a member of Kennedy's inner circle. Many liberal Democrats were skeptical of him as a southerner and a Washington operator. But Johnson "was able to turn the country's grief into a commitment to a moral crusade," presidential scholar Jeffrey Tulis has written. It took him longer than 100 days, but Johnson set Congress on the path to passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as well as a tax cut and Medicare. Actually, he sought to pass more legislation, help more people, lift more Americans out of poverty, and become more of a historic figure than FDR. And in some ways, he succeeded, under a program he called the Great Society.

Ronald Reagan

In November 1980, Ronald Reagan was elected president in a landslide over Democratic incumbent Jimmy Carter.

Americans decided that the country, driven by economic distress and international embarrassment, needed a big change and that Reagan's conservative, government-is-the-problem philosophy was worth a try.

Reagan began with a whirl of activity. But it was different from Roosevelt's approach in 1933, in that the new Republican president decided he had to set priorities and not load up the system with a plethora of bills.

In February 1981, he sent to Congress what many political scientists called some of the most sweeping revisions of budget and tax policy ever attempted. The cornerstones of his plan were an across-the-board tax cut and an effort to reduce the size and growth of the federal government.

Reagan had argued for years that government was getting too powerful and intrusive. This was his chance to convert his rhetoric into action, and that's what he did.

In the first few weeks after Reagan submitted the proposals, they sparked enormous controversy and powerful opposition.

Many critics said the president was trying to do nothing less than destroy Roosevelt's activist-government legacy from the New Deal.

The critics also warned that Reagan was overestimating the revenue that his economic plans would generate and that this would set the stage for huge budget deficits later. Those warnings proved prescient. But at the time, frustrated Americans were ready to do things Reagan's way.

It took Reagan more than 100 days to get his program of tax cuts and less government through Congress, but he did succeed. And many historians say it was his first 100 days that paved the way.

President Reagan was able to bond with middle America in part by surviving an assassination attempt with grit and good humor and by showing his determination to keep pushing until his program got through.

AMERICAN POLITICS

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Receive our political analysis by email by subscribing here

© Tribune Media Services